TABLE 1

Description of Variables and Predictions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.21 |

.40 + |

|

|

|

.26 |

.44 + |

|

|

|

.27 |

.45 + |

|

|

|

.14 |

.35 + |

|

|

|

12.84 |

|

|

|

|

29.69 |

17.10 + |

|

|

|

8,657 |

10,557 + |

|

|

|

.45 |

.50 + |

|

|

|

.04 |

.19 + |

|

|

|

.48 |

.50 + |

|

|

|

27.46 |

|

|

|

|

.80 |

.40 + |

|

|

|

.42 |

.49 + |

|

|

|

.01 |

.08 + |

|

|

|

472,687 |

499,073 + |

|

|

|

53.84 |

11.01 + |

|

|

|

1,508 |

|

|

|

|

.14 |

.35 + |

|

|

|

.08 |

.27 + |

|

|

|

2,964 |

2,771 + |

|

|

|

.23 |

.42 + |

|

|

|

.08 |

.27 + |

TABLE 2

the 1970-1974 Cohort of Immigrants, Untied States, 1980

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(54,189)

(20,253)

(8,995)

(34,357)

(21,218)

(20,089)

(5,111)

(1,710)

(952)

(20,793)

(43,783)

(17,365)

(1,496)

TABLE 2 (Continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28.1 |

(34,887) |

|

|

25.9 |

(48,550) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

57.6 |

(552) |

|

|

26.6 |

(82,885) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

25.8 |

(17,862) |

|

|

27.4 |

(45,137) |

|

|

26.4 |

(20,438) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

29.8 |

(4,051) |

|

|

29.2 |

(23,232) |

|

|

32.3 |

(28,666) |

|

|

18.6 |

(27,488) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

31.1 |

(6,599) |

|

|

26.3 |

(55,161) |

|

|

26.7 |

(21,677) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

31.8 |

(11,939) |

|

|

26.0 |

(71,848) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

26.8 |

(6,589) |

|

|

26.8 |

(76,848) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19.1 |

(33,192) |

|

|

25.7 |

(25,544) |

|

|

38.3 |

(24,701) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

31.5 |

(19,605) |

|

|

25.3 |

(63,832) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30.7 |

(6,385) |

|

|

26.5 |

(77,052) |

TABLE 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odds |

|

|

Odds |

|

|

Odds |

|

|

|

|

Ratio |

|

|

Ratio |

|

|

Ratio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.818 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.723 |

|

|

|

|

3.289 |

|

|

|

|

|

2.943 |

|

|

|

|

3.683 |

|

|

|

|

|

3.384 |

|

|

|

|

2.578 |

|

|

|

|

|

3.621 |

|

|

|

|

1.038 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.053 |

|

|

|

|

.999 |

|

|

|

|

|

.998 |

|

|

|

|

1.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.001 |

|

|

|

|

1.022 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.020 |

|

|

|

|

1.348 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.294 |

|

|

|

|

1.080 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.046 |

|

|

|

|

.862 |

|

|

|

|

|

.896 |

|

|

|

|

1.029 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.021 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.150 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.181 |

|

|

|

|

1.106 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.136 |

|

|

|

|

3.562 |

|

|

|

|

|

3.228 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.006) |

1.034 |

|

|

1.077 |

|

|

|

|

|

(.001) |

1.011 |

|

|

1.011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.006) |

.978 |

|

|

.924 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.036) |

1.299 |

|

|

1.282 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.048) |

1.111 |

|

|

1.146 |

|

|

|

|

(.005) |

1.196 |

|

|

1.162 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.021) |

.965 |

|

|

.725 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(.034) |

.775 |

|

|

.799 |

|

|

|

|

.041 |

|

(.118) |

.077 |

|

|

.008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

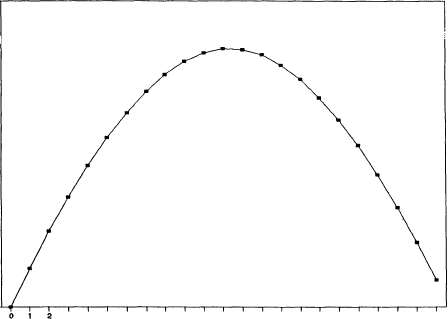

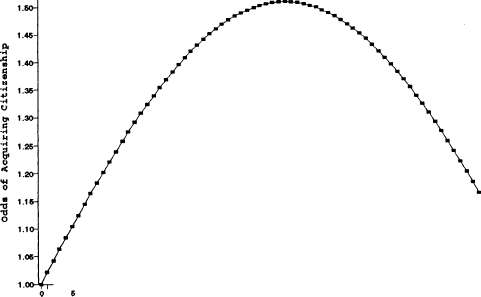

FIGURE II

Revisited," Ethnicity, 7:159-190.

21:390-405.

Migration Review, 22:243-264.

ess," International Migration Review, 15:608-625.