Hoon K. Lee

Union Christian College, Pyengyang, Korea

*An extract from a study of the pioneer belts of Manchuria, one of a series of studies of migration and land use in pioneer belts of the world being conducted under the auspices of the American Geographical Society. This extract presents preliminary conclusions of the author, a Korean, based on intensive fieldwork carried on under conditions of extreme difficulty in 1031.

196

Four Pioneer Belts

S -.-.МБ.-. """

Ю0 200KIL0METER5

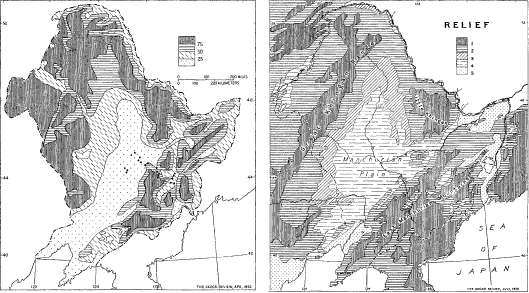

Fig. з Fig. 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Peking-Mukden Line . . . 3. Kaiyuan 4. Mukden-Hailung Line . . . 5. Changchun-Kungchuling 6. Szepingkai-Taonan Line . . 7. Kirin-Changchun Line . . 8. Chientao 9. Southern Branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway 10. Harbin 11. Eastern Branch of the Chi nese Eastern Railway . . . 12. Lower Sungari 13. Hulan-Hailin Line .... 14. Western Branch of the Chi nese Eastern Railway . . . 15. Northern Manchuria and other localities |

7,057,270 2,335,6oo 2,808,140 1,206,160 2,620,200 1,297,730 1,253,070 578,000 2,111,300 475,490 1,149,150 1,899,490 1,389,230 2,791,980 225,110 |

218 343 333 132 359 72 66 38 195 2,353 48 53 97 3i 1 |

1,206 823 804 949 671 403 503 578 406 3,396 385 412 366 319 89 |

|

Total Population and Average |

29,198,020 |

78 |

590 |

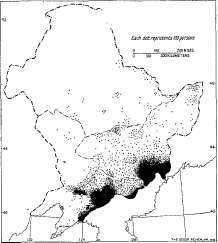

Koreans in Manchuria

The Kando District

Routes to the Interior

A Field Study in Central Kirin